The portrait of the leader is a symbol of the image of the party and a symbol of the legitimacy of the regime. As early as the Soviet period, the CCP focused on using portraits of leaders. The portraits of leaders at the time were relatively s more of a self-expression of the nature of the party. The promotion of Mao Zedong’s political status is closely related to his rising party status. Whether in the ideological field or within the social system, Mao Zedong has established absolute authority and become the highest leader in practical terms (Hung 416). In the image below, a portrait poster of Mao made in 1951 is shown. The facial area of the portrait is especially highlighted. There is almost a sense of divinity shining through the image. This agrees with the political background of China back then. At the village level, Mao Zedong used political momentum such as military victories and land reforms and became a worship idol for rural China. The biggest difference between the portrait of Mao Zedong and any previous image of an emperor or leader is that it enters every corner of society with the widest scope, including factories, schools, hospitals, stations, government agencies and other social organizations at all levels and places.

Chairman Mao Zedong, 1951, Unknown Artist

Portraits made before 1976 were mainly controlled by the state, to show the admiration for the greatness of the leader. People even took a proactive approach to embrace Mao’s portraits widely and deeply into the private space. From the mid-late 50s to the 60s, this method of hanging portraits of Chairman Mao at home has entered a state of fanaticism. The portrait of Mao Zedong has replaced the ancestors, genealogy, images of gods and traditional scrolls in the family space (Hung 421). The political purpose was to establish the legitimacy of the party rule in the Mao era. With the changes in the anti-Japanese war situation and the political situation, the CCP gradually realized the importance of publicizing the image of the regime. It consciously alienated and weakened the portraits of leaders such as Sun Yat-sen and paid attention to the portrait and use of its own leaders. After systematic political manipulations, Mao Zedong, as a symbol of revolutionary government, are deeply imprinted as a collective memory of the people, which greatly consolidated the power of the CCP.

In the late Mao era, western artists began to use the image of Mao Zedong in delivering their own artistic messages. Andy Warhol’s series of Mao portraits is representative among these works. Initially, Warhol made a portrait of Mao with the red and yellow colors, which was different from the mainstream Chinese portrayal of the leader. This was done when former US president Nixon first visit China in an ice-breaking trip (Gewirtz). By breaking the conventional image of Mao, Warhol may have intended to symbolize the initiation of a new era for China to open up and embrace market economy. To a large extent, it can also be said that Mao Zedong gave the original inspiration to political pop about China. China’s political pop is clearly affected by the US Pop art.

Mao, 1972, Andy Warhol

The orientation and presentation of China’s political pop are largely contrary to the US version. The features of Pop in the United States are to strengthen or even deify the popular images, such as the Coca-Cola cans and the movie star Marilyn Monroe. Political pop of Mao is precisely the vulgarization and popularization of the divine image. In addition, conventional pop in the United States has promoted popular culture to something elegant, while Andy Warhol’s has been altering the divine image of Mao to something popular, colorful, and even amusing (Lago 47). But the problem is that in the context of China, Mao Zedong is still a special symbol. The political implications of Mao’s images are inherent. Choosing Mao Zedong as the theme, it is unavoidable for any artist to become political about it. Therefore, no matter whether it is a joke or humor, the Mao image of the political pop by Warhol has always expressed a sense of historical or realistic criticism.

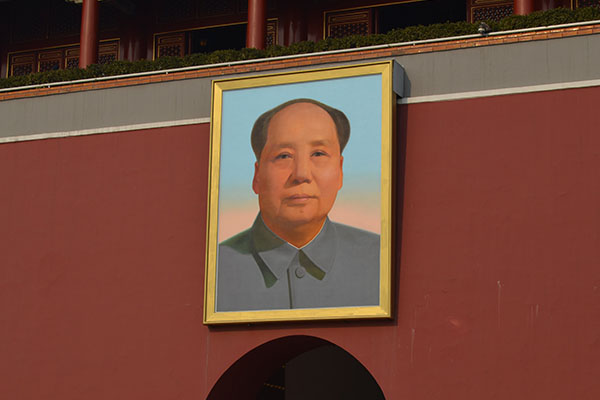

With the death of Mao Zedong in 1976, Mao Zedong as the physical subject naturally ceased to exist. The death of Mao Zedong was a turning point in the history of Mao Zedong’s image construction process in China. Although there are still ordinary folks who worship Mao Zedong, this phenomenon is merely an expression of dissatisfaction with certain aspects of the reality and does not have practical significance. However, it needs to be understood that Mao Zedong’s historical status is unshakable even in the present. The CCP has found a new narrative, which is reflected in Mao’s images. In the 2016 portrait of Mao placed at the Tiananmen Square, the divinity of Mao and the worship was replaced. Instead of the highlights, bright eyes, and pop colors, the “aggressiveness” in the portrait is tuned down and replaced with a mild, gentle father or grandfather figure.

Newly Replaced Portrait of Mao in Beijing, 2016, Unknown Artist

After Mao’s death, the rights and wrongs of Mao have often been judged. However, different leaders have also adopted different attitudes towards the issue. Unlike the straightforward way Deng Xiaoping talked about the mistakes Mao once made, Xi Jinping has adopted a more pro-Mao attitude. Some even consider him the leader closest to Mao’s style (Denyer). As for the consistent ambiguity and almost secrecy nature of Mao Zedong’s portraits at the Tiananmen Square, people are guided to understand that these portraits of Mao Zedong at Tiananmen are not intended to be viewed as artificial works. They are more likely to be interpreted as a self-changing living body. The change of portrait seems to be a person’s natural aging process